Crime, Policing, and Voter Turnout

Bill McCarthy (Rutgers University-Newark), John Hagan (Northwestern University), Daniel Herda (Merrimack College)

Politicians love to talk about crime in their election campaigns. The conventional wisdom is that tough-on-crime solutions will bring out the vote. Chicago’s recent mayoral elections showed this perfectly, when several candidates promised to reduce crime through increased policing. Yet researchers disagree about how crime and policing are connected to voter turnout. We analyze data from Chicago’s last two mayoral elections to clarify.

Some research argues that crime encourages voter turnout. It can motivate victims and those afraid of crime to show their support for crime-focused politicians. Anger, a desire for empowerment, or wanting to hold incumbents accountable may encourage political engagement and increase turnout, especially in municipal elections.

Other research predicts the opposite, arguing that rising crime discourages turnout. Crime encourages anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and despair. These feelings reduce political efficacy and increase political detachment and dissatisfaction with local politics. These patterns may be pronounced when voters believe that violent crime is particularly acute.

Scholars also disagree about how policing influences turnout. Some say that police neglect, misconduct, or aggressive tactics, such as stop-and-frisk and the use of force, may encourage voter turnout. Anger and a desire to hold police and elected officials accountable may also bring out the vote. Conversely, other scholars argue that harsh policing erodes trust in government, intensifies political alienation, lowers political efficacy, and encourages political and civic withdrawal.

Testing the links between neighborhood crime, policing, and voting is complicated because it’s not just what goes on in your neighborhood that matters: what is happening in the adjacent neighborhood can spill over. For example, voter turnout in low crime neighborhoods may be influenced by higher crime communities a few blocks away. Voter turnout is strongly associated with demographics like age, gender, education, income, race, and ethnicity, and it may also be influenced by these same attributes in neighboring communities.

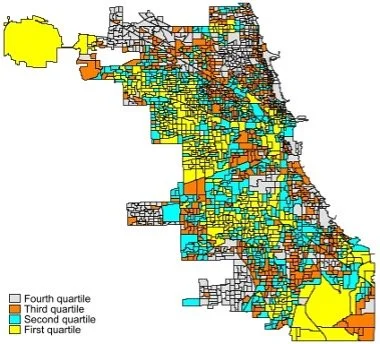

We find these “spillover” effects in Chicago’s 2019 and 2023 mayoral elections. Figure 1 shows maps of voter turnout provided by the Chicago Board of Elections. The maps indicate the Chicago election precincts (black lines) and voter turnout, divided into quartiles. The colors correspond to turnout levels: grey precincts have the highest turnout, yellow are the lowest, and those shaded in cyan and orange are in the second and third highest, respectively. There is considerable clustering, with higher voter turnout concentrated in the northern parts of the city and lower turnout in the west and southwest.

Figure 1: Voter turnout by quartiles, Chicago 2023 (n=1,291), General Mayoral Elections, by Electoral Precincts. 2023 General Election

Figure 2: Voter turnout by quartiles, 2019 (n=2,069) General Mayoral Elections, by Electoral Precincts. 2019 General Election

We measure crime, police stops, and complaints about the police with records from the City of Chicago data portal and the Invisible Institute's Citizens Police Data Project. These variables were measured three years prior to each election to account for yearly fluctuations. Our analysis also includes several common predictors of voter turnout gathered from the US Census.

Overall, the results show that voter turnout is lower in neighborhoods where violent and property crime are high. Similarly, voters are also more likely to stay home on election day in neighborhoods with more frequent police stops. In contrast, a greater number of police misbehavior complaints seem to increase voter turnout. These relationships are evident in both the 2023 and 2019 elections and hold even after considering the neighborhood spatial relationships and other common predictors of voter turnout.

Collectively, the negative relationship between crime and voter turnout suggests that politicians who focus on crime may deter, rather than encourage, voters. Meanwhile, the negative association between turnout and police stops and the positive association between turnout and complaints about police misconduct suggests that focusing electoral campaigns on calls for more policing may backfire on the tough-on-crime candidates.

Bill McCarthy works in the Rutgers Newark School of Criminal Justice. His recent research focuses on homelessness and policing and has appeared in the Annual Review of Criminology, Race and Justice, Law & Social Inquiry, Theoretical Criminology, and Criminology.

John Hagan is John D. MacArthur Professor Emeritus at Northwestern University. He and co-author Alberto Palloni published mortality estimates of the Darfur genocide in Science in 2006. He is the co-author of Darfur and the Crime of Genocide, with Wenona Rymond-Richmond, Mean Streets: Youth Crime and Homelessness, with Bill McCarthy, and, most recently, Chicago's Reckoning: Racism, Politics, and the Deep History of Policing in an American City, with Bill McCarthy and Daniel Herda.

Daniel Herda is a professor of sociology, academic dean, and co-director of the School of Arts and Sciences at Merrimack College. His research focuses mostly on international migration, particularly the areas of immigrant adaptation and factual misperceptions among members of the receiving society. His recent projects have focused on the concepts of reactive ethnicity and reactive transnationalism. Dr. Herda's latest work has been published in International Migration Review, Global Networks, and International Migration.