Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) in Philadelphia and their Potential as Regional Actors

Richardson Dilworth (Drexel University)

Editor's Note: This essay is part of the STATE OF THE FIELD - American Regionalism and the Constellation of Mechanisms for Cross-Boundary Cooperation colloquium.

Highly localized business improvement districts (BIDs) may seem like an unlikely entry in a colloquium on regional governance. However, in this piece, Richardson Dilworth (Drexel University) invites us to consider how BIDs exist as a form of collective action that, like other types of regional entities, form to leverage common resources to solve problems and seize opportunities that do not easily correspond to political jurisdictions. He argues that whether these organizations are cross-boundary (as some are) or fully contained within a single jurisdiction, their origin stories and experiences can offer lessons to observers of American regionalism. Furthermore, he speculates that BIDs may have the potential to evolve along several pathways to participate in processes: either through generating hyperlocal cross-boundary organizations, forming federations or blocs, or by establishing chains of related and similarly designed regional entities across a metropolitan area. These offer tantalizing insights into how the regional governance landscape might evolve from below. Finally, Dilworth injects a critical perspective, noting that even as cross-boundary partnerships are mechanisms of collective action and cooperation, they are also (mostly unintentionally) instruments of exclusion and fragmentation to the extent that they focus benefits internally. This is a theme that is also worth considering across the other contributions to this colloquium.

Business improvement districts (BIDs) are special service and assessment districts that typically cover territories as large as the downtown of a central city or as small as the commercial corridor of an outlying neighborhood. These organizations typically collect mandatory fees – assessments – from property owners within their areas to fund projects and provide services such as cleaning streets, providing security, installing streetscape improvements, and marketing the area. BIDs operate at a highly localized scale but, like many regional entities, they are a form of collective action that can cross jurisdictional boundaries. So, while they are rarely considered as a form of regionalism, they may have an overlooked role in cross-boundary governance. Furthermore, these cross-boundary BIDs are among the constellation of actors involved in governing American regions. In the context of this colloquium on American regionalism it is worth exploring the experience of BIDs, and their cross-boundary variants, and reflect on their place in urban and regional development.

In the first part of this essay, I develop a brief and admittedly highly stylized comparison of BIDs and regional entities to suggest that these two types of organizations share more in common than typically thought. Second, I provide a brief history of BIDs in Philadelphia; and third, I focus on the two intermunicipal BIDs, namely the City Avenue Special Services District and the short-lived Greater Cheltenham Avenue Business Improvement District, to explain the specific ways in which either organization functions or functioned as a regional entity. In a final and even more speculative section, I suggest that it is in fact the larger and more successful central city BIDs that may pose a more promising path for regional intergovernmental activity than do intermunicipal, cross-boundary BIDs.

The Evolution of BIDs and Regional Entities

Post-World War II urban development in the United States has been the subject of ample research, focusing especially on how the Great Migration of Black Southerners and subsequent White flight to the rapidly growing suburbs was (and still is) related to housing and transportation policy (Glotzer 2020; Nall 2018, ch. 2), education policy (Logan, Zhang, and Oakley 2017), and segregation (Leibbrand et. al. 2020). One outcome of all these various developments was, as Jessica Trounstine (2018) has documented, that “Neighborhoods became more racially integrated within cities, but whole cities became more racially homogeneous, increasing segregation between them.” (p. 21)

The rapid growth of regional entities, especially the development of RIGOs, is part of the story of postwar urban development that does not obviously fit the story of increasingly balkanized metropolitan regions composed of municipalities divided by race and class. Indeed, as organizations typically responsible for coordinating among municipalities in metropolitan regions, RIGOs would appear to reflect the opposite of the fragmentary impulses that defined postwar urbanization. Yet in other respects, RIGOs arguably reinforced metropolitan fragmentation by providing a mechanism for intermunicipal coordination over some policies, most notably transportation, while also allowing municipalities independence in the very areas that allowed them to maintain economic and racial segregation, most notably with respect to public school districts and zoning (see, for instance, Taylor 2019, 162-171, 281-286).

Similar to RIGOs, BIDs do not at first glance appear relevant to the story of postwar metropolitan fragmentation, yet they are arguably in large part a continuation of that fragmentation. More often discussed in the context of later phenomena such as gentrification and neoliberal urban policy (see, for instance, Schaller 2019), BIDs were a product of the 1970s, first appearing in US cities that had been losing population and business, such as New Orleans (home of the first-known downtown BID in the US) and New York City (for a broad overview of BIDs see Stokes and Martinez 2020). They proliferated in the 1990s; for instance, Philadelphia’s first BID, the Center City District, was established in 1990 and was followed by the South Street Headhouse District in 1992, the Frankford Special Services District and Germantown Special Services District in 1995, Manayunk Special Services District in 1997, and the Old City District and City Avenue District in 1998.

In nearly every instance, the purpose of these BIDs was to provide additional services, primarily security and street cleaning, for a relatively small territory by levying a new assessment on properties in that territory. Citywide property taxes are typically charged as a flat percentage rate and are thus not a good tool for taxing wealthier areas at their full capacity, especially in cities with high income inequality, which was increasingly true of Philadelphia and other cities, especially in the 1990s (Philadelphia in Focus 2003, 56). BIDs, which in most instances cover relatively high-value territories, are mechanisms for capturing excess property tax capacity that cannot be captured by a citywide tax, and using that extra capacity only for services in the territory. This is notably also one of the chief competitive advantages that many suburbs have with respect to central cities – they are wealthier, more economically homogeneous, and cover smaller territories, meaning that they can capture a greater amount of their tax capacity and use those taxes to provide goods, primarily good public schools, that better match the preferences of their residents.

In short, if RIGOs and other regional entities reinforced the fragmentation of metropolitan areas into central cities and numerous surrounding suburbs, BIDs were one small effort at fragmenting those central cities into what are effectively suburban municipal overlays on cities. In short, although neither form intended to exacerbate fragmentation or inequality, RIGOs and BIDs are similar in the sense that they were organizational adaptations that found interestingly symmetrical roles for themselves in the postwar evolution of US metropolitan regions. This is important for my purposes here because Philadelphia’s two cross-boundary BIDs appear to be organizational mutations that blend together the adaptive strategies of both RIGOs and BIDs and thus suggest an alternate evolutionary path.

A Brief History of BIDs in Philadelphia

Though BIDs were not established in North America until the 1970s, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a Business Improvement District Act (BIDA) in 1967, authorizing municipal governments to establish districts in which benefitted property owners could be charged an assessment that would pay for primarily physical improvements. Whether any BIDs were actually formed under this law is unclear – also unclear is why the BIDA explicitly excluded Philadelphia, the state’s largest city. When the first BID was established in Philadelphia – the Center City District (CCD), in 1990 – it was authorized under an earlier law, the 1945 Municipality Authorities Act (MAA). (Morçöl and Patrick 2008, 297-302; Hoffman and Houstoun 2010, 92-93)

The MAA had traditionally been used as a tool to finance, build, and manage such things as water and sewer systems, hospitals, and public school buildings, through special authorities that, unlike BIDs, often do cover multiple municipalities. Amendments to the MAA in 1980 allowed municipalities to create BIDs as municipal authorities. The municipalities that first took advantage of these new provisions were Pennsylvania’s mid-sized cities – places like McKeesport, Media, Pottstown, and Conshohocken. Big cities followed, mostly in the 1990s, including the CCD, but also the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, which was established as a BID in 1997 (Morcol and Patrick 2008, 302-304).

As I noted above, a quick succession of other BIDs formed in Philadelphia in the 1990s after the establishment of the CCD; and in accordance with my argument that BIDs have often been used to “lock in” neighborhood wealth for the exclusive purposes of wealthier neighborhoods, those established in Philadelphia typically covered either established or gentrifying commercial districts that served upper-income clientele. Two exceptions that prove the rule were the Germantown and Frankford BIDs, notable for serving the main commercial corridors of lower income neighborhoods. Both BIDs were ultimately dissolved – two out of three established in Philadelphia that have not survived (the third is one of the cross-boundary BIDs, discussed below). The reasons for the dissolution of either BID are somewhat complicated and place-specific (see Stokes 2006; 2010; Kummerow 2010; McCabe 2019) but they certainly suggest the limits to which BIDs might serve as tools of economic uplift, for which other neighborhood-based organizations such as community development corporations may be more appropriate (Imbroscio 2006, 229-230).

Under the leadership of Paul Levy, the CCD became a nationally recognized model for downtown BIDs, and CCD personnel were active in helping to establish other BIDs in Philadelphia (though the CCD remains unique among the city’s BIDs in that it is far larger in terms of territory, budget, personnel, and functions). As a result, most BIDs have followed the CCD model, most importantly in terms of collecting assessments. Typically, a municipality will include the BID assessment in the larger property tax bill and then transfer the assessment to the BID. By contrast, given both the unwillingness of the Philadelphia Department of Revenue to collect BID assessments, and a lack of trust among Center City property owners in the capacity of the city government (part of the motivation for proposing a BID in the first place), the CCD agreed that it would collect assessments itself, as have all subsequent BIDs in the city.

In 1998 the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed the Community and Economic Improvement Act (CEIA), for establishing BIDs specifically in Philadelphia, and in 2000, the Neighborhood Improvement District Act (NIDA), for establishing BIDs elsewhere in the state. Under both laws, BID governance was made more flexible than under the MAA. For instance, BIDs established as municipal authorities have boards of directors appointed by the city government, in the case of Philadelphia the City Council, whereas under the CEIA board appointments are specified in the authorizing ordinance (cross-boundary BIDs have boards composed of equal numbers of representatives from either municipality, and are authorized by separate ordinances in each municipality). In theory BIDs established under the MAA have slightly different powers, such as to issue bonds, though in practice the authorizing legislation has not been the determinative factor defining BID functions or powers. Under both the NIDA and CEIA, BIDs are governed by nonprofit corporations, designated as NID management associations. BIDs are created by municipal ordinance, and they must be approved through a negative vote, meaning that at least 51 percent (changes to the law have now made it one-third) of property owners in the affected district must file a remonstrance with the city clerk to object to the establishment of the BID. If the BID passes the vote it is authorized for five years, after which it can be reauthorized through the same process for a period of 20 years (Morçöl and Patrick 2008; Dilworth 2016).

Under CEIA, eight new BIDs were created in Philadelphia in the first decade of the 21st Century: The East Passyunk BID (2002), Port Richmond Industrial Development Enterprise (2003), Roxborough District (2003), Chestnut Hill District (2004), Mount Airy BID (2007), Frankford Special Services District (which had briefly disbanded and was recreated under the CEIA in 2007, then disbanded again in 2010), Aramingo Shopping District (2008), and Greater Cheltenham Avenue BID (2010), which, like the City Avenue District, was a cross-boundary BID. By 2010 there were 14 BIDs operating in the city, under either the MAA or CEIA (Houstoun and Hoffman 2010).

Perhaps inspired by the antitax rhetoric reflected as well in the rise of the Tea Party, several BID proposals after 2010 were rejected or else did not move forward due to a concern that they would be rejected. Early in 2012 a proposal to establish a BID in the Callowhill neighborhood north of Center City was the first ever to be rejected in the mandatory vote among district property owners. In the same year a proposed North Central Neighborhood Improvement District around Temple University met enough local resistance that it was never reported out of committee in City Council. Other BID proposals, including one for Chinatown and one for the Washington Square West neighborhood of Center City that would have been funded through assessments on homeowners rather than commercial or rental properties, were rejected at the community level before ever reaching City Council. More recently there has been a resurgence in BID formation. In 2015 a BID was established for the main commercial corridor of the Mayfair neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia, and BIDs were established in the adjacent and gentrified neighborhoods of Northern Liberties and Fishtown in 2017 and 2019, respectively (Blumgart 2019; Dilworth 2016).

Cross-boundary BIDs

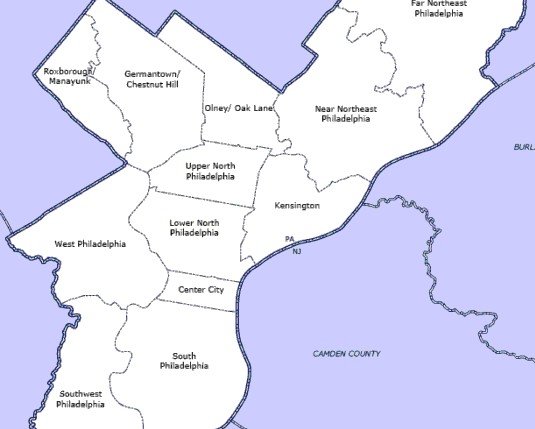

Philadelphia’s 130-square mile territory is roughly in the shape of the letter Y. The city’s two cross-boundary BIDs (only one of which still survives) are the City Avenue Special Services District (CASSD), which covers an autocentric commercial corridor that also defines part of the Philadelphia’s Western boundary with Lower Merion Township, along the upper stem of the Y; and the Greater Cheltenham Avenue Business Improvement District (GCABID), which covered a wide road, Cheltenham Avenue, that formed part of the city’s Northwestern boundary with Cheltenham Township, along the left interior of the upper part of the Y. Cheltenham Avenue’s most prominent features within the GCABID territory were two shopping malls on the Cheltenham side of the Avenue. The BID’s territory also extended South into Philadelphia, to cover a portion of the commercial corridor along Ogontz Avenue in the West Oak Lane neighborhood.

Given that there are thousands of BIDs in the world there are undoubtedly others that cross municipal boundaries, but the only ones that have been written about are the CASSD, the GCABID, and a BID in London known as We Are Waterloo, that includes territories in two separate councils, Lambeth and Southwark (Santer 2008). When the CASSD was created in 1999, its director David Cohen claimed that “of the more than 1,600 special-services districts nationally … City Avenue is the first and only to serve two jurisdictions” (quoted in Greenstein 2001).

The most notable difference between Philadelphia’s two cross-boundary BIDs is that the CASSD is still a thriving organization while the GCABID largely failed to actualize - at least on the Philadelphia side, the Cheltenham component of the BID survived for at least some time. The reasons for the success of the CASSD and the failure of the GCABID have never been explored. Based on the known antagonisms between cities and suburbs in the US, one obvious hypothesis is that the failure of the GCABID resulted from there being greater racial and economic disparities between Philadelphia and Cheltenham than there are between Philadelphia and Lower Merion.

It is, in fact, the opposite: the racial and economic disparities are greater in the CASSD territory than they were in the GCABID territory. The three Philadelphia zip codes (19126, 19138, and 19150) that included the GCABID have a median family income of $40,429 and are 91 percent Black, while the two zip codes on the Cheltenham side (19095 and 19027) have a median household income of $68,482 and are 35 percent Black. In the case of the CASSD, the Philadelphia zip code (19131) that includes the district has a median household income of $27,914 and is 79.1 percent Black, while the two Lower Merion zip codes (19004 and 19066) have a median household income of $148,322 and are 2.9 percent Black.

There are at least four more compelling hypotheses that explain the relative success of the CASSD. First, the boundary between Philadelphia and Lower Merion that is also the heart of the BID is a large street named City Avenue which was designed after World War II to be a car-centric commercial corridor with stores primarily in shopping malls (most notably the upscale Bala Shopping Center) that were more connected to the Avenue itself than to the surrounding neighborhoods (Greenstein 2001).

Second, the primary reason that most stakeholders wanted to establish the CASSD was because of increasing crime on City Avenue, and that crime was seen as in part a function of the very fact that the commercial corridor straddled a municipal boundary line, which impeded the work of the police on either side (Palus 2010). For instance, state representative Lita Cohen (one of the early supporters and founders of the BID) described a ride-along she took with Lower Merion police who pursued a suspected thief that crossed over to Philadelphia, when “We stopped. We screeched to a halt. It was Philadelphia's problem” (quoted in Greenstein 2001). Philadelphia and Lower Merion police used different radio frequencies, though with the coordinating help of the CASSD they switched to the same frequency and used the BID as part of an agreement to allow officers from either municipality to work on either side of the boundary, along with security officers on bike patrols hired by the CASSD (Greenstein 2001).

Third, the very fact that it was a state representative who was one of the early proponents of the BID was significant. Lita Cohen’s legislative district was entirely on the Lower Merion side of the boundary, yet as a state official she was one step removed from local politics and thus more capable of serving as a neutral party. Fourth and finally, City Avenue was a focal point of the campus of Saint Joseph’s University, a midsized school with approximately 8,000 students, located on both sides of the Avenue. Given its student body and the centrality of City Avenue to its campus, Saint Joseph’s had a particular interest in the appearance and safety of the corridor. The university president took an active interest in supporting the BID since “the university represents one-fourth of the real estate value in the district. Plus, it's easier to attract students to a campus in a vital neighborhood than in a ‘tattered’ one” (Greenstein 2001).

Notably, hardly any of these conditions existed along Cheltenham Avenue. Like the CASSD, one of the earlier supporters of the GCABID was a state House representative, Dwight Evans, but the similarity ends there. As the longstanding Democratic chair of the Pennsylvania House Appropriations Committee, Evans was uniquely powerful and well-known for his work on economic development in and around the Ogontz Avenue commercial corridor, most notably for founding the Ogontz Avenue Revitalization Corporation (OARC), which hosted the West Oak Lane Jazz and Arts Festival from 2003 to 2011, generously funded through state grants. Unlike City Avenue, however, the heart of the Ogontz Avenue commercial corridor is pedestrian friendly and lies entirely in Philadelphia, though it does intersect with Cheltenham Avenue, which forms the boundary between Philadelphia and Cheltenham Township. Yet on Cheltenham Avenue virtually all of the commercial property is on the Cheltenham side, and located almost exclusively in two shopping centers: Greenleaf at Cheltenham (known as Cheltenham Plaza at the time of the GCABID) and the sprawling Cedarbrook Plaza Shopping Center (Wheeland 2010).

It was, in fact, only township officials and some property owners in Cheltenham that were initially interested in establishing a BID, but who were turned down for a state grant to do so by the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (PADCED). Looking to emulate what they saw as the success of the CASSD, PADCED officials encouraged Cheltenham and Philadelphia officials to work together on a joint BID, which on the Philadelphia side was handled almost entirely by Evans and OARC. The primary hope from the PADCED side was that a BID would help with the redesign of Cheltenham Plaza, which was underperforming and had a large and underutilized parking lot (Bednar 2013).

One of the more striking aspects of the GCABID was that, despite the fact that Philadelphia businesses would be getting much of the services for the BID but would be contributing less in assessments than Cheltenham property owners, resistance to the BID was primarily among property owners on the Philadelphia side. According to one state official who was involved in the GCABID effort, the chief resistance among those on the Philadelphia side were chain restaurants who already had advertising and employees who cleaned sidewalks and thus did not see the benefit of a BID, and marginal business owners who were worried about new assessments. The primary supporters were the neighborhood churches – who as nonprofits would not have been subject to the assessments (Bednar 2013; Wheeland 2010).

Regardless of opposition on the Philadelphia side, the BID passed in the Philadelphia City Council with the support of the district councilwoman Marian Tasco, but then was never established for two primary reasons: First, just as the BID was being established the Great Recession hit and made businesses even more reluctant to accept new assessments (as I noted previously, the period immediately after the Great Recession saw more concerted resistance to new BIDs). Second, Dwight Evans suffered a series of setbacks as he and OARC were connected to a series of questionable decisions regarding state spending, ultimately leading Evans to lose his powerful leadership position on the House appropriations committee in 2010 (Zitcer and Dilworth 2019). As a result, GCABID was effectively stalled on the Philadelphia side, even as the BID was established on the Cheltenham side – ironically what Cheltenham officials had sought in the first place.

In the case of the GCABID, Cheltenham Avenue was not considered the center of a cross-boundary commercial corridor, the boundary line itself was not considered a problem that could be solved with a BID, and there was no institution similar to St. Joseph’s, a relatively large institution that straddled the boundary line and had a vested interest in the appearance and safety of the boundary-line avenue. There was, in short, no sense of a shared asset between Philadelphia and Cheltenham Township that could serve as the basis for a cross-boundary BID.

Conclusion: Future Mutations

The development of CASSD and the attempt to launch GCABID as multi-jurisdictional BIDs are admittedly rare cases, but these cases highlight how BIDs could evolve beyond their present forms. This potential evolution permits new angles to probe our theories of regional interaction. I conclude with some propositions to consider should BIDs move in this direction: How could the presence of multijurisdictional BIDs alter relations among the municipalities? Could multijurisdictional BIDs (or BIDs with regional reach as described below) become new nodes in the regional network, and if they could, what could we expect their influence on that network to be?

As we consider how multi-jurisdictional BIDs could affect the relations among municipalities, the intergovernmental nature of the CASSD is qualified by the extent to which its primary responsibility is to a commercial corridor that stands apart from both the municipalities it occupies. It is in this respect possibly vaguely more similar to the joint governing body of a demilitarized zone between two countries rather than a truly intergovernmental organization. Had the GCABID succeeded, it would have been more intergovernmental in nature in the sense that it would have brought together two municipalities that did not previously share a common sense of purpose. Whether the GCABID could have succeeded also begs the question of whether an intergovernmental organization such as a cross-boundary BID can somehow be used to create, rather than simply be a response to, a shared sense of purpose between neighboring municipalities.

The circumstances leading to the establishment of the CASSD are relatively rare and thus the potential for its model of cross-boundary BID governance to diffuse to other areas seems somewhat low. Yet there are at least two other potential avenues by which normal BIDs that don’t cross boundaries might function as actors of note in regional governance. First, if there are enough BIDs spread across municipalities in a metropolitan area, those BIDs might join together to become a new kind of regional entity – in effect a shadow council of governments or a regional chamber of commerce, but with powers of direct taxation (or at least property assessment, which in the case of BIDs is typically considered a user fee and not a tax). In several cities – for instance in Washington, DC and New York City – there are BID councils that represent the collective interests of all BIDs in the city, funded through contributions by the BIDs (Philadelphia’s BIDs are in fact in the process of establishing their own council). These BID councils are typically non-profit organizations not strictly bound to the geographic constraints of their cities and could easily include suburban BIDs as members, thereby becoming potentially regional in scope.

Second, a dominant city BID with an enviable reputation for success, such as the CCD, might effectively extend its control into the suburbs by taking control of suburban BID management associations (BIDMAs or NIDMAs, the non-profits that actually operate the BIDs). The CCD could do this through a franchising model, using its reputation to sell a prepackaged set of branded strategies and services to suburban BIDMAs. In this way, the CCD would become a central node in regional networks uniquely positioned to affect implementation and development of economic activity and policy. A more straightforward approach would be a chain rather than franchise model, whereby suburban BIDMAs would simply be created as corporate subsidiaries to the CCD.

The idea that downtown central city BIDs might become regional by establishing chains of suburban BIDs or franchising to those BIDs is hardly on the agenda in any metropolitan area. But in the organizational evolution of urbanization, ideas often serve as the random mutations that under the right circumstance might be selected and reproduced (Lewis and Steinmo 2012). Thus, key to that organizational evolutionary process is that people continuously propose new ideas. Yet evolution is also a random, contingent, and directionless process that does not automatically connect to desired policy outcomes. This is especially true of BIDs, which in the case of Philadelphia have been almost exclusively successful in wealthier neighborhoods. A broader network of BIDs that stretched across a metropolitan region might simply compound some of the very problems we might hope regional coordination could ameliorate, namely economic and racial segregation. At the same time, BIDs can often function more nimbly than general purpose municipalities, and in some instances, they have tackled larger social problems (see Bergheiser 2016) so there seems some possibility that they might somehow be steered in more constructive directions at a regional level.

References

Bednar, Robert. 2013. Interview with the author. November 21.

Bergheiser, Matt. 2016. “Why Your Commercial District Needs an Anti-Poverty Strategy.” Next

City, February 4. https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/bids-commercial-district-anti-poverty-strategy-job-opportunity

Blumgart, Jake. 2019. “Despite loud opposition, business improvement districts for Fishtown, South Philly advance.” Plan Philly WHYY. October 17. https://whyy.org/articles/despite-loud-opposition-business-improvement-districts-for-fishtown-south-philly-advance/?fbclid=IwAR29QifW_l_zqUpyP4fwAwmIdgufsqItQykyuBUyWQk6MUVVOeOkEcvweHw

Dilworth, Richardson. 2016. “The Past, Present, and Future of Business Improvement Districts in Philadelphia.” Drexel Policy Notes 2 (Winter): 3-11. https://drexel.edu/~/media/Files/coas2/pub_pol/DPN_Winter16_v3.ashx?la=en

Philadelphia In Focus: A Profile from Census 2000. 2003. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Center for Urban and Metropolitan Policy.

Glotzer, Paige. 2020. How the Suburbs Were Segregated: Developers and the Business of Exclusionary Housing, 1890-1960. New York: Columbia University Press.

Greenstein, Louis. 2001. “Lower Merion, Philadelphia Become Allies.” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 12, B5.

Hoffman, Daniel, and Houston, Lawrence O., Jr. 2010. “Business Improvement Districts as a Tool for Improving Philadelphia’s Economy.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 89-108.

Imbroscio, David. 2006. “Shaming the Inside Game: A Critique of the Liberal Expansionist Approach to Addressing Urban Problems.” Urban Affairs Review 42 (November): 224-248.

Kummerow, Whitney. 2010. “Finding Opportunity While Meeting Needs: The Frankford Special Services District.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 243-252.

Leibbrand, Christine, Massey, Catherine, Alexander, J. Trent, Genadek, Katie R., and Tolnay,Stewart. 2020. “The Great Migration and Residential Segregation in American Cities during the Twentieth Century.” Social Science History 44 (Spring): 19-55.

Levy, Paul. 2010. “Business Improvement Districts in Philadelphia: A Practitioner’s Perspective.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 71-88.

Lewis, Orion, and Steinmo, Sven. 2012. “How Institutions Evolve: Evolutionary Theory and Institutional Change.” Polity 44: 314-339.

Logan, John R., Zhang, Weiwei, and Oakley Deirdre. 2017. “Court Orders, White Flight, and School District Segregation,” Social Forces 95 (March): 1049-1075.

McCabe, C. 2019. “Germantown Business Owners, Frustrated by Trash, Vote to Dismantle the Agency that Cleaned their Streets.” Philadelphia Inquirer. June 20. https://www.inquirer.com/news/germantown-special-services-district-reauthorization-fail-business-owners-frustrated-trash-cindy-bass-20190620.html

Miller, David, and Nelles, Jen. 2020. “Order Out of Chaos: The Case for a New Conceptualization of the Cross-boundary Instruments of American Regionalism.” Urban Affairs Review 56: 325-359

Morçöl, Göktuğ, and Patrick, Patricia A. 2008. “Business Improvement Districts in Pennsylvania: Implications for Democratic Metropolitan Governance.” Pp. 289-318 in Business Improvement Districts: Research, Theories, and Controversies. eds. Morçöl, Göktuğ, Lorlene Hoyt, Jack W. Meek, and Ulf Zimmerman. New York: CRC Press.

Nall, Clayton. 2018. The Road to Inequality: How the Federal Highway Program Polarized America and Undermined Cities. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Palus, Christine Kelleher. 2010. “There is No Line: The City Avenue Special Services District.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 287-307.

Santer, Helen. 2008. “Cross-borough Business Improvement Districts: Waterloo’s Attempt to Become the First Town Centre BID to Cross a Local Authority Boundary.” Local Economy 23 (February): 81-85.

Schaller, Susanna F. 2019. Business Improvement Districts and the Contradictions of Placemaking: BID Urbanism in Washington, D.C. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Stokes, Robert J., and Martinez, Julia. 2020. “Business Improvement Districts.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Urban Studies, ed. Richardson Dilworth. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780190922481-0009. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stokes, Robert. 2010. “The Challenges of Using BIDs in Lower-income Areas: The Case of Germantown, Philadelphia.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 325-338.

Stokes, Robert. 2006. “Business Improvement Districts and Inner-City Revitalization: The Case of Philadelphia's Frankford Special Services District.” International Journal of Public Administration 29 (August): 173-186.

Taylor, Zack. 2019. Shaping the Metropolis: Institutions and Urbanization in the United States and Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

Trounstine, Jessica. 2018. Segregation by Design: Local Politics an Inequality in American Cities. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wheeland, Craig. 2010. “The Greater Cheltenham Avenue Business Improvement District: Fostering Business and Creating Community Across City and Suburb.” Drexel Law Review 3 (Fall): 357-372.

Zitcer, Andrew, and Dilworth, Richardson. 2019. “Grocery Cooperatives as Governing Institutions in Neighborhood Commercial Corridors.” Urban Affairs Review 55 (March): 558-590.For more information about how we are using language in this colloquium, see this file.