Social and Political Pillars of Police Diversity

Police officers serve a public service role, as highlighted by scholarly literature on street-level bureaucracy. Thus, it matters whether police departments represent the social characteristics of communities. In socially diverse cities, police diversity promises to facilitate police–community interactions. However, to what extent are US police departments diversifying their personnel?

Policing Now, Gentrification Later?

Aggressive policing has hidden costs. This study provides some of the first empirical evidence that intensified policing can lead to gentrification. Our findings challenge conventional wisdom about the causes of neighborhood change and offer a crucial lens to understand how law enforcement policies shape the places we live—sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically.

As cities confront issues of inequality, racial justice, and housing displacement, studies like this reveal why rethinking public safety is not just about crime—it's about who has the right to belong in a neighborhood.

Crime, Policing, and Voter Turnout

Politicians love to talk about crime in their election campaigns. The conventional wisdom is that tough-on-crime solutions will bring out the vote. Chicago’s recent mayoral elections showed this perfectly, when several candidates promised to reduce crime through increased policing. Yet researchers disagree about how crime and policing are connected to voter turnout. We analyze data from Chicago’s last two mayoral elections to clarify.

Security is on the upswing; who should get the credit?

Every three months, the Mexican National Statistics Institute (INEGI) publishes information on public safety perceptions for Mexico’s 96 most populated cities. About three years ago, in July 2022, right after INEGI published this data, the former Mexico City head of government and now president Claudia Sheinbaum, turned to Twitter to share some great news. She tweeted that perceptions of public safety continued to improve in the city thanks to her public safety and policing strategies. Several hours later, borough mayor Santiago Taboada made a similar claim (for context, Mexico City is divided into sixteen boroughs, each with its elected borough mayor). Taboada tweeted that residents of his borough ranked it as one of the safest in the country thanks to his policing model, which he called Blindar BJ or Protect Benito Juarez. For those familiar with Mexico City, Taboada’s tweet does not really make sense and is somewhat puzzling, given that security in the city is provided by the Mexico City police, an entity that was then accountable to Sheinbaum.

60.6

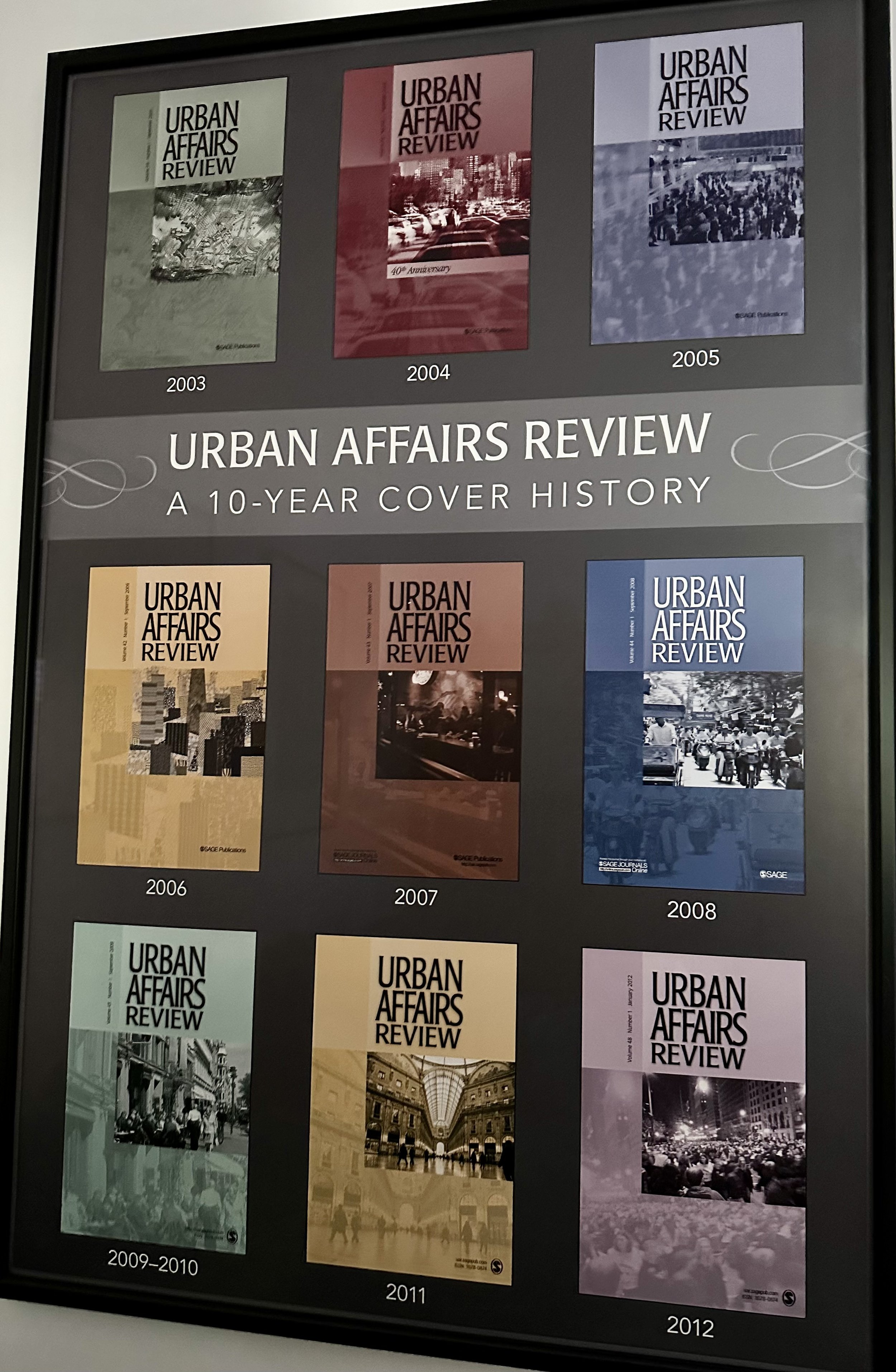

Issue 6 of our anniversary volume features an introductory essay by managing editors Christina Greer and Tim Weaver. Featuring Zoltan Hajnal and Jessica Trounstine's 2013 article, “What Underlies Urban Politics? Race, Class, Ideology, Partisanship, and the Urban Vote,” along with a new essay by Hajnal and Trounstine reflecting on their influential work today.

60.5

Issue 5 of our anniversary volume features an introductory essay by managing editors Maureen Donaghy (Rutgers University-Camden) and Yue Zhang (University of Illinois-Chicago). Featuring Jefferey Sellers’ 2005 article, “Re-placing the Nation,” along with a recent essay by Dr. Sellers on urban comparative politics. We’re also pleased to share a wonderful essay by former UAR editors Susan Clarke and Michael Pagano that reflects on their long tenure as editors and the changes in the field.

60.4

Issue 4 of our anniversary volume features an introductory essay by managing editors Maureen Donaghy (Rutgers University-Camden) and Yue Zhang (University of Illinois-Chicago). We revisit Larry Bennett’s “Harold Washington and the Black Urban Regime,” which was published in Urban Affairs Review in 1993.

60.3

Issue 3 of our anniversary volume features an introductory essay by managing editors Christina Greer (Fordham University) and Tim Weaver (University at Albany). We revisit Elinor Ostrom’s “The Social Stratification-Government Inequality Thesis Explored,” which was published in Urban Affairs Review in 1983.

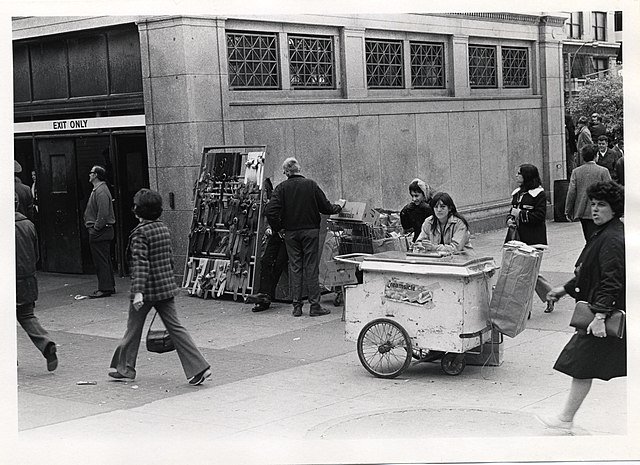

Reform and Community Level Participation

Eleven years after the official over turn of Stop, Question, and Frisk (SQF) in New York City there is still a debate about the appropriate ways for officers to interact with citizens on the street – and what information they have a right or obligation to record. How police stops impact citizens and their wider communities is of critical importance, but difficult to fully understand until long after policies have unfolded. However, within the bounds of privacy, detailed data on police actions and where they occur can provide the needed information to trace back how effective policy changes are and what consequences they have.

60.2

Issue 2 of our anniversary volume features an introductory essay by managing editors Richardson Dilworth (Drexel University) and Mara Sidney (Rutgers University-Newark). We revisit Michael Lipsky’s “Street-Level Bureaucracy and the Analysis of Urban Reform” published in Urban Affairs Quarterly in 1971.

Are dollar stores magnets for violent crime?

In recent years, the United States has experienced a significant rise in economic inequality, a trend that has coincided with the rapid expansion of dollar stores, especially in the aftermath of the Great Recession. These establishments are often lauded as beacons of affordability, providing essential goods to financially disadvantaged communities. However, recent media reports and community demonstrations have cast a shadow on their presence. They highlight several concerning aspects, one of which is an alleged escalation in violent crimes in their vicinity.

Experiences of policing in gentrifying neighborhoods

Cities in the United States are well known for their segregation and sharply different experiences of policing across neighborhood boundaries. Extensive social science research has shown that “race-class subjugated neighborhoods” with concentrated populations of low-income Black and Latino residents experience harsh and punitive policing, whereas high-income and mostly-white neighborhoods experience limited police contact. In the former neighborhoods, residents also express frustration that policing does not address concerns about crime or violence, leading to these neighborhoods being simultaneously “over-policed and under-protected.”

“Defund” or “Refund” the Police?

In June of 2020, like many of you, we watched as George Floyd died at the hands of the Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. We also watched as countless residents of cities took to the streets to protest this injustice. At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic meant that most city council meetings were being held via Zoom. In meeting after meeting, we observed calls to defund the police or move funds to other departments. While popular media reported that most departments did not defund their police budgets, the narrative and the rhetoric persisted. We wondered: to what extent might local governments have reduced their police budgets in the aftermath of the protests?

From Rejection to Legitimation

In April 2021, the City of Portland, Oregon legalized sanctioned, self-managed houseless encampments. It did so in a very pedestrian manner, by amending its land use ordinances that regulate houseless camping in order to make encampments amenable with the city code. This is a big deal! Currently, the regulatory responses by municipalities experiencing high numbers of unsheltered houselessness is quite varied.

Policing Temporality

Numerous studies have shown how gentrification processes promote and are supported by an increase in policing. Areas under gentrification are subject to more intensive police presence, stop-and-arrest practices, aggressive police tactics and surveillance. These claims are raised by long-term residents who suffer from and witness intensified police presence in their neighborhoods, and are also supported by empirical data on 311 calls to police and by qualitative studies with new residents who admit for demanding more police presence.

Officer-Involved Killings and the Repression of Protest

It is clear from the news, and perhaps even from personal experience, that many citizens are mobilizing to express outrage and demand justice in the wake of officer-involved killings. However, despite the fact that officer-involved killings are the focus of such an important social movement, very little work attempts to explain the circumstances that lead the public to protest the deaths of particular victims.

Understanding the Adoption and Implementation of Body-Worn Cameras among U.S. Local Police Departments

Police use of deadly force against racial minority residents is a major concern of U.S. policing. The several high-profile police-involved deaths of racial minority residents, such as the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson and the death of Eric Garner in New York City, along with the acquittal of police officers involved in those incidents, led to minority residents’ riots and looting in protest of police brutality. These incidents and the resulting public outcry brought major national debate on officers’ discriminatory treatment toward Black people and pressured the governments to devise a way to control officers’ discretionary decision to use of deadly force.

Exploitative Revenues, Law Enforcement, and the Quality of Government Service

One aspect of recent criticism of police departments has been centered on the aggressive imposition and collection of fees, fines, and civilly forfeited assets. The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) investigation of the Ferguson, Missouri police department, for example, revealed that a key driver of the behavior of the Ferguson police was the desire to generate municipal revenue by issuing traffic tickets and imposing fees. More broadly, a growing body of evidence indicates that local police departments are being used to provide revenue for municipalities by imposing and collecting fees, fines, and asset forfeitures.

Recidivism and Neighborhood Governance

Prisoner re-entry and recidivism pose significant challenges for many of our most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Ex-offenders face such disadvantages as weakened family and social relationships, outdated skills, stigma in the labor market, and psychological trauma from prison experience. The social isolation and economic vulnerability that ex-offenders face spills over into their neighborhoods, reinforcing neighborhood poverty and weakening local social institutions. At the same time, neighborhood poverty and other forms of disadvantage create barriers to successful re-entry and make it more likely that an ex-prisoner will re-offend. These findings lead many researchers to conclude that cycles of incarceration and re-entry reinforce neighborhood disadvantage in many communities.