The Future of Collaborative Leadership in Contemporary Regional Entities

George Dougherty (University of Pittsburgh) and Suzanne Leland (University of North Carolina at Charlotte)

Editor’s Note:

This contribution by George Dougherty (University of Pittsburgh) and Suzanne Leland (University of North Carolina at Charlotte) reminds us that although the landscapes of American regional activity are populated by organizations, those organizations are made up of people. While we often discuss these organizations in the abstract – as entities with agendas, and responsibilities, capacity, and legal agency – these are decided on and executed by individuals. As this piece highlights, the people that lead these organizations often have years (and sometimes decades) of experience and are often instrumental in facilitating the kinds of activities that we take for granted that RIGOs, and other regional entities, can perform. In this context, the coming wave of executive director retirements, and the weakness of succession planning, may impact organizational effectiveness and could potentially diminish regional capacity. Observers of American regionalism should be aware of leadership transitions in these organizations and be prepared to study their potential effects on regional governance and collective action. More broadly, this is one of many potential threats to effective regions and serves as a reminder that regional collaboration should not be taken for granted. As organizations like RIGOs evolve, their trajectories will not necessarily involve a linear intensification of regionalism. The sources of dynamics such as intensification and retrenchment, and their link to internal factors like leadership, is an important gap in our knowledge base.

Preserving leadership, institutional knowledge, and intergovernmental relationships are key to solving the wicked problems that do not stop at jurisdictional boundaries. Talent is a valued commodity and high turnover is a problem. Regional Intergovernmental Organizations (RIGOs) and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) are no exception. To continue leading collaboration in our regions, it is important to invest in future leadership and talent for future generations. As the population ages, contemporary organizations need to recruit and mentor new talent. However, we know little about the succession planning process in these organizations. So how do we know where to invest or if we are investing enough in public employees if there are no benchmarks? And to what extent is this a problem for the future of these organizations?

The problem would seem pressing based on demographic trends and related professions. About 10,000 people in the U.S. turn 65 every day (AARP, 2021). The International City County Manager’s Association in 2009 reported that 63 percent of city and county managers were over 51 years of age with most expecting to retire within the near future (ICMA 2009). A 2010 study of nonprofit Executive Directors in Charlotte, North Carolina found that 61% of Executive Directors were over 51 years of age with 51 percent expecting to retire within five years and 18 percent expecting to leave for another job soon (Carman, Leland & Wilson, 2010). According to the US Office of Personnel Management, 101,580 federal employees retired in 2019. We would expect this trend carries over to Regional Intergovernmental Organizations (RIGOs) and Metropolitan Planning Organizations but have little information.

Finding Talent to Fit the Regional Setting

Succession planning in urban areas has a direct impact on organizational effectiveness and planning. Organizations need talent to be successful in the short and long-term. Whether it is a payroll clerk, a professional planner, or an Executive Director, it seems logical that an agency or firm is more likely to accomplish its mission if employees have the skills, training, experience, and motivation necessary. Organizations in fields with many firms or whose employees largely come from clear professional tracks usually attempt to find the best and brightest among an established talent pool and make adjustments to their skills and training once hired. In fields with specialized missions, few firms, and less direct links to standard practice in professions or trades, organizations may need to be more proactive to find, train, develop, and motivate employees to accomplish their mission. While succession planning is important for all organizations, it would seem even more critical for organizations in the latter scenario, especially when hiring an Executive Director.

Regional Intergovernmental Organizations (RIGOs) and MPOs fall in the latter category of organizations with less clear links to professions and preparation for promotion. For example, many RIGOs provide transportation planning services and need employees with a background in civil engineering. There are approximately 303,000 civil engineers in the United States and 52,000 firms in the heavy and civil engineering construction sector. These professionals develop skills and expertise to build our roads and bridges. Hiring the most skilled engineers is the goal of those 52,000 firms. Finding those with the skills to negotiate, design, and fund transportation systems across multiple jurisdictions and levels of government represented by hundreds of elected officials is the goal for the 470 or so RIGOs across the nation. The latter would seem a more difficult task requiring a more thoughtful process.

Finding an Executive Director for a RIGO would seem more difficult still. RIGOs play important roles in multiple policy areas, so an Executive Director needs to lead an organization that may coordinate transportation planning alongside Area Agency on Aging services, water and soil conservation, and economic development while providing rural broadband services to outlying communities. And while an un- or under-qualified hire at a private firm can devastate a business and its employees, the consequences of hiring a poorly qualified RIGO Executive Director reverberate across numerous local jurisdictions and the lives of hundreds of thousands or millions of residents.

Executive Directors Matter, But Who is Responsible for Succession Planning?

All of this assumes that Executive Directors are particularly important to organization performance. This assumption is confirmed by the literature which notes that agency performance improves when executives perceived as ineffective are dismissed and that organization performance often suffers immediately after an executive change. The few studies that exist suggest that succession planning can help organizations avoid hiring ineffective Executive Directors in the first place, minimize the initial disruption of executive transitions, and prepare for long-term effectiveness by providing the organizational and environmental autonomy needed to make necessary changes in organization behavior.

Like Executive Directors of RIGOs, city and county managers and nonprofit Executive Directors share governance responsibility with boards. Responsibility for succession planning is unclear in both of these settings. The limited literature available on nonprofits suggests Executive Directors see succession planning as a key responsibility for their boards. Boards may disagree or fail to act on this responsibility as only 23 percent were found to have a succession plan in 2010 (Carman, Leland, & Wilson 2010). Further, small nonprofits with flat structures leave young employees few opportunities for career advancement and unprepared for Executive Director positions when they become available. Other research indicates that boards often underestimate the consequences of bad hiring decisions at the Executive Director level and therefore fail to invest appropriate resources ahead of time or during an Executive Director search (Carman, Leland, & Wilson 2010).

Research on succession planning in the local government sector is sparse, but only 14 percent of North Carolina cities and counties had a succession plan in place in one study (Leland, Carman, and Schwartz 2012). Further, only 25 percent of city and county managers saw succession planning as one of their central duties. As Leland, Carman, and Schwartz (2012) note “We find no evidence that managers are actually concerned about finding their replacement.” (p. 48) Elected boards present other concerns. Limited time horizons due to electoral cycles make long-term planning seem beyond the scope of elected officials’ many concerns. Elected officials’ decades long efforts to “do more with less” has left many city and county governments too lean with limited ability to do anything beyond their regular duties. Cost cutting has also resulted in fewer assistant manager positions available to prepare the next generation of managers to step up. And given the highly politicized environment of government, many elected officials and managers are unsure how to frame or carry out succession planning, resulting in most preferring to avoid the issue altogether. As with nonprofit organizations, few in the local governments that turn to RIGOs to provide regional leadership have had any experience with succession planning.

Based on what we know about succession planning in the nonprofit and local government sectors, we expect RIGOs to experience the worst of both worlds. First, there is no a priorireason to believe RIGOs have clarity on whether the Executive Director or the board is responsible for succession planning. Absent this clarity, succession planning is likely to be rare. If RIGO Executive Directors come from the ranks of nonprofit Executive Directors or city and county managers, their training and prior experience would suggest succession planning is not a priority. Boards made up primarily of elected officials suffer from short time horizons and highly politicized environments. This is exacerbated as the primary focus of elected officials is their local jurisdiction rather than the region. RIGOs also suffer from their lean operations. Miller, Nelles, Dougherty & Rickabaugh’s (2018) book, Discovering American Regionalism, reports the average RIGO staff size at 21 employees with 52 percent of RIGOs employing fewer than 15 employees. This suggests there are few opportunities to advance and many lack management experience. Finally, few board members or Executive Directors have more than limited experience with succession planning.

Building an Evidence Base

The truth is, we do not know much about RIGOs or other regional entities, such as MPOs or RPOs and even less about the individuals that lead them. A key first step is to explore who the Executive Directors are and how they arrived at their current positions. Information about their age and length of service can help predict how many RIGOs could benefit from succession planning efforts soon. Knowing their career paths and academic training will provide some insight into the qualifications past boards found important when hiring an Executive Director. Answers to questions about their job satisfaction and sense of effectiveness could prove instructive on which of these personal characteristics are most important to executive turnover.

To explore these questions, we conducted a survey of executive directors of regional entities such as COGs, MPOs, RPCs, and RPOs. Contact information was gathered from the RIGO database, state agencies and professional associations, and individual organization web sites, resulting in a population of 583 RIGOs and MPOs included. Executive directors from 246 of these organizations responded to the survey with 223 completing the survey in its entirety. The goal of the survey was to understand the composition of these organizations and what they have been doing to ensure leadership into the future. The survey received promotional support of National Association of Development Organizations (NADO) and National Association of Regional Councils (NARC).

The study revealed that Executive Directors are similar to local government managers across the U.S. in terms of age and suffer from the same demographic issues as many local governments. Approximately 65 percent of Executive Directors are over 51 years old and 29 percent are over 60 years of age. As Table 1 shows, we found a clear lack racial and ethnic diversity among respondents as over 91 percent were white. In terms of gender diversity, we were encouraged that they were composed of about 26 percent female and 62 percent male, with women making up 32 percent of Executive Directors under 50 years of age.

Table 1. Race & Ethnicity of Regional Executive Directors

Previous studies noted that regional Executive Directors are sensitive to and reject the notion that they are “another layer of government.” Few of these organizations have the power to tax, so they do not show up in the Federal Census of Governments. However, when asked whether their organization is primarily chartered as a governmental, nonprofit, private, or other type of organization, over 74 percent indicated they were governmental with the remainder choosing the nonprofit option.

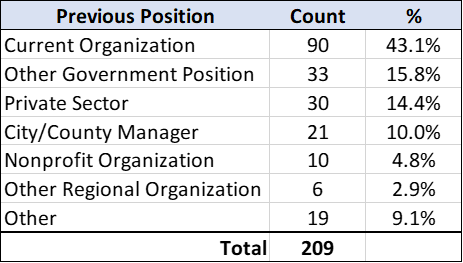

It is not surprising then that Executive Directors seldom came from anywhere other than regional entities or government organizations. The most common path to the executive directorship was promotion from within (43.1 percent) with an additional 2.9 percent hired from other regional entities. Other Executive Directors held previous jobs with government agencies (15.8 percent) or served as city or county managers (10 percent). As noted above, these career paths are not likely to have given them much experience with succession planning.

Table 2. Previous Position Before Becoming Executive Director

Turnover and Succession Planning Activities

It is important to understand whether organization characteristics affect RIGOs ability to plan for and then manage Executive Director transitions to ensure continuity in regional collaborative efforts. Unfortunately, the picture of the future is bleak if we are relying on long-term leadership in regional entities. Over 40 percent of the current Executive Directors plan to leave in five years or less. Sixty-five percent of those surveyed are 51 and over with only ten percent of all executive directors aged forty and under. This level of turnover suggests future troubles sustaining regional leadership over the next decade, especially when combined with routine board membership changes due to electoral cycles at the local level.

Table 3. Expected Tenure and Age of Regional Executive Directors

In fact, turnover is already an issue in RIGOs and MPOs. According to survey respondents, over 60 percent of these organizations have had two or more executive directors and an alarming 26 percent have had three or more directors in the past decade. And while the average tenure in their organization was around ten years, that figure is skewed by the 41 respondents (18.1 percent) that have served as Executive Directors between twenty and thirty-seven years.

Despite their recent histories with Executive Director turnover and an impending wave of Executive Directors planning to leave in the next five years, a relatively small portion of RIGOs and MPOs seem concerned about turnover. Only 22 percent of respondents indicated their boards had discussed turnover in the past two years. Further, Table 4 shows that turnover concerns are more likely to focus on staff (approximately 54 percent “Somewhat concerned” or “Very concerned”) than executive-level employees (approximately 38 percent “Somewhat concerned” or “Very concerned”). Taken together, these results confirm those found in the local government and nonprofit literatures suggesting neither regional boards nor Executive Directors are likely to focus heavily on succession planning.

Table 4. Concern with Executive-Level and Staff Turnover

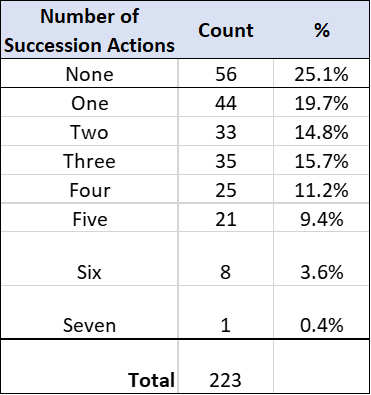

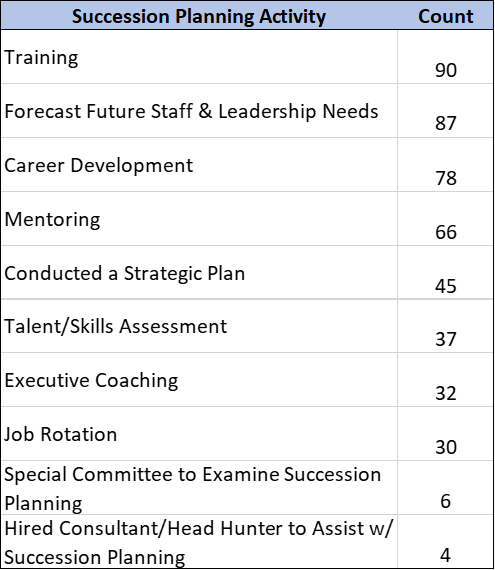

Survey results show that RIGOs and MPOs are taking some steps related to succession planning. As Table 5 shows, 25 percent of RIGOs have not engaged in any succession planning activities. We found that the most common succession planning activity is to conduct training, followed by forecasting future staff and leadership needs. Less frequent are mentoring, strategic planning, talent/skills assessment, executive coaching, and job rotation. While many of these activities may be introduced for reasons other than succession planning (ex. Training or Mentoring), they do have the effect of improving prospects of success among future Executive Directors and therefore organizational performance.

Table 5. Number of Succession Planning Activities

Table 6. Succession Planning Activities Utilized

Conclusion

Due to our intergovernmental system and large number of local governments, regional entities (RIGOs, MPOs, and RPOs) are the necessary glue to hold together regional collaboration. This is especially highlighted in policy areas such as planning, economic development, transportation, environment and aging. The literature indicates that succession planning contributes to overall organizational performance. The results of this exploratory survey of executive directors demonstrates the need for more succession planning activities in regional entities similar to the need among local governments and nonprofits. This is especially true with respect to executive directors.

Many regional entities are engaged in training and forecasting leadership needs, which is a great start. Executive turnover is an acute problem as baby boomers continue to retire, but the data indicates there is still an opportunity for these organizations to expand and embrace succession planning activities. The majority of organizations in this study are concerned about turnover at the staff level, but not as much as the executive level. This is disconcerting given the high turnover rates in the last ten years and the number of Executive Directors planning to leave in the next few years. The profession must ensure stable and expert leadership through a variety of succession planning activities and investment in current employees to better prepare for future success.

Given the importance of leadership in convening and coordinating regional activities, establishing strategic directions for regional activities, and brokering relationships – all of which require considerable experience, trust, and soft skills – these trends could have important consequences for regional entities. At worst, inexperience might lead to organizational mismanagement or failure. However, short of that, inexperienced leadership could lead to an erosion of trust in the organization, a reduction or withdrawal from setting regional agendas, or a resumption of hostile parochialism. While Miller and Nelles note that some RIGOs have been around for over 50 years and may be better situated to weather temporary leadership struggles, this is not the case for all organizations some of which are more vulnerable than others. As RIGOs continue to evolve, their momentum in some cases will be threatened by leadership change. It will be vital for observers of American regionalism to consider leadership among the factors that explain emerging regional agendas, their successes and failures, and to understand how these seemingly pedestrian personnel concerns may have profound consequences.

The survey presented here is a first step in understanding succession planning in regional entities. We plan a qualitative follow up study using focus groups and interviews with executive directors of these organizations to generate new ideas, explore the feasibility of specific succession planning activities, find models of best practices for regional entities.

References

American Association of retired Persons (AARP). https://arc.aarpinternational.org/countries/united-states accessed on June1, 2021.

Carman, J. G., Leland, S. M., & Wilson, A. J. (2010). Crisis in leadership or failure to plan? Insights from Charlotte, North Carolina. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 21(1), 93-111.

Leland, S. M., Carman, J. G., & Swartz, N. J. (2012). Understanding managerial succession planning at the local level: A study of the opportunities and challenges facing cities and counties. National Civic Review, 101(2), 44-50.

ICMA (2009). State of the Profession Survey. https://icma.org/documents/icma-survey-research-2009-state-profession-survey

Miller, D., Nelles, J., Dougherty, G., & Rickabaugh, J. (2018). Discovering American regionalism: An introduction to regional intergovernmental organizations. Routledge.