Increasing Minimum Teacher Salaries

One might be hard-pressed to turn on the evening news these days and avoid reports of some form of staffing shortage, a phenomenon which seems to cut across a myriad of professions ranging from bus drivers to hospital nurses. Public school teachers fall squarely in this concern, particularly in school districts that serve the largest shares of low-income students, often in urban and rural locales. How might public policymaking address the teacher workforce to reduce shortages, improve longevity, and reestablish its stature? In our work, we examine a pandemic-era salary reform in Missouri, home to one of the nation’s worst teacher salary landscapes, where starting, full-time public school teacher salaries can be as low as $25,000.

Partisanship and Professionalization

Since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, school board operations - and the elections to those positions - have received increased attention nationally and locally. As we realized the central role school boards were playing in the political landscape, we wanted to better understand how school boards were responding to both the pandemic and being increasingly in the political spotlight. We conducted a large-scale survey of school board members in multiple states during the summer of 2021. In open-ended responses on the survey, school board members highlighted their frustration with the politicization of the pandemic.

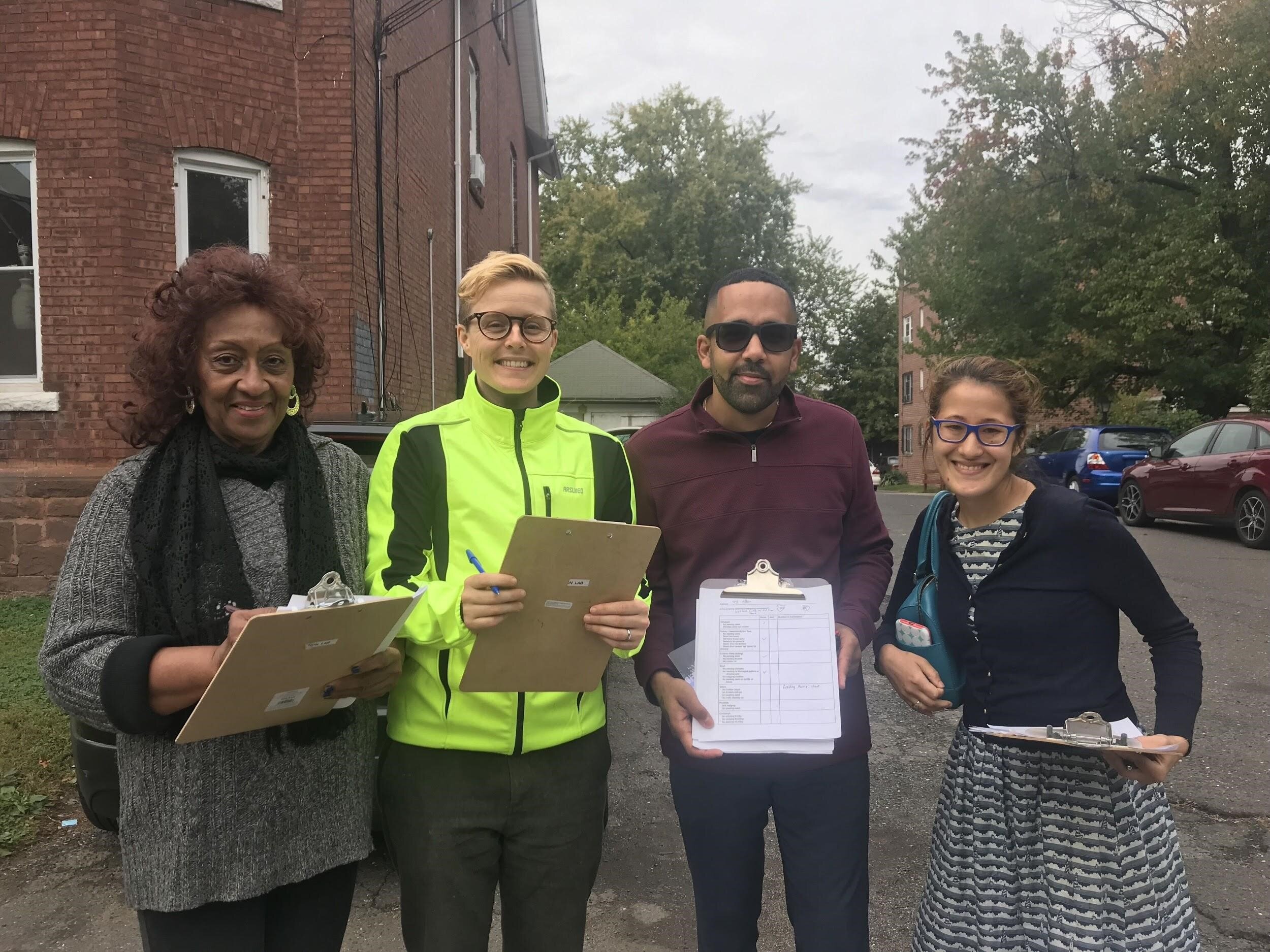

InnovateGov in Detroit

On July 18, 2013, the City of Detroit filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, the largest U.S. municipality to declare bankruptcy. The city’s financial crisis had severe consequences for the day-to-day operations of city government -- diminishing capacity to collect taxes, to respond to blight in neighborhoods, and to provide a baseline of public services and social supports. Through the InnovateGov program, we have developed a way to connect Michigan State University’s (MSU) most vital resource -- talented and motivated students -- to local government agencies and nonprofits charged with governing post-bankruptcy Detroit.

The Importance of Service Learning

When I arrived at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) and learned I had the freedom to incorporate service learning into my courses, I leapt at the opportunity to educate my students on the importance of community engagement and the hands-on application of the material we discussed in class, for multiple reasons. Service learning in undergrad allowed me to know my local community better, delve deeper into social science theories surrounding the issues related to the communities in which I served (education policy, the politics of disaster relief, etc.), and working as a team to accomplish important tasks in the broader community.

The Liberal Arts Action Lab

At traditional academic research centers, faculty and graduate students make decisions on what topics to study. The Liberal Arts Action Lab reverses roles by empowering local residents of Hartford, Connecticut to drive this process. Prospective community partners from different neighborhood groups and non-profit organizations submit one-page proposals about real-world problems they wish to solve. All must agree to share their proposals on a public web page, designed to share -- rather than hide -- what different organizations are planning to work on.

Right Cause, Wrong Method?

There is widespread agreement among educational stakeholders on the urgency of school improvement. Educational actors ranging from policymakers, educators, parents to non-profit organizations and corporations insist that the public school system has failed too many underprivileged children and improving struggling schools is a central challenge in public education.

Preserving Education as a Public Good

On October 19, 2017, Bill Gates announced that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation would invest $1.7 billion in education with 60% going for curricula development and network building among schools, 15% for charter schools, and 25% for “big bets that have the potential to change the trajectory of public education over the next 10 to 15 years.” (quoted in L. Camera, 2017). Less than one month later, on November 16, 2017, the School Reform Commission (SRC), the body set up by the Pennsylvania legislature to govern the Philadelphia School District, voted to dissolve itself, returning school governance to Philadelphia[1] This vote was the result of intense grassroots activism involving thousands of teachers, nurses, school aides, students, parents, and other activists.

Flipping a Small Classroom

I knew I was in trouble. I was teaching my new elective Public Sector Communications for the first time. I meticulously planned assignments – group work, active discussions, a comprehensive project. That first night, there were four people in the room – myself and three (eek!) master of public administration students. I went home and realized almost everything I had planned would not work.I went back the next week and asked the students for their help. I said I wanted to flip the classroom – something I had never tried before – and would do it only if they agreed and were willing to work with me along the way. We gave it a try.

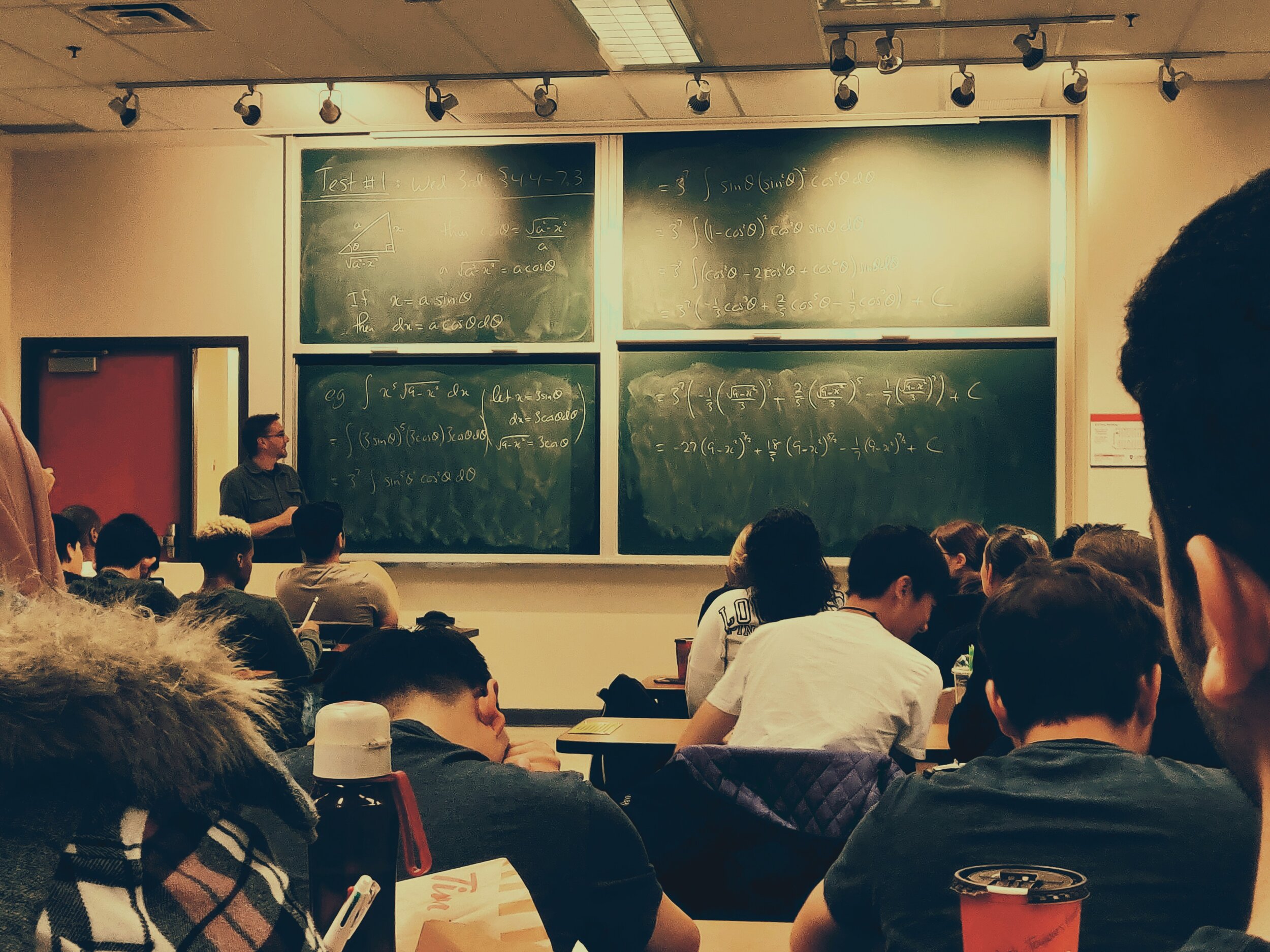

Engaging in Active Learning: Mock Political Campaigns

Teaching Political Science can be extremely content heavy, so it is a struggle to “flip the classroom,” in which the students complete the content material at home in order to have a hands-on experience within the class. I created a group project where the students participate in a mock-political campaign. While this focused on a National Campaign, this could be adapted to a local election context as well. This project aligns with the Student Learning Outcome of students will understand the political process. In order for this group project to be effective, I used weekly scaffolding activities to hold the students accountable. In addition, you should create weekly Student Learning Outcomes that would align with the student understanding a segment of the political process.

Private Governance of Public Schools

Charter schools now operate in 43 states and the District of Columbia and their numbers have grown significantly. In most school districts, there are only a handful of charter schools that operate alongside traditional neighborhood-based public schools. However, in 14 urban districts, over 30 percent of the students are enrolled in a charter school. At 93 percent of its public school students in charters, New Orleans tops this list.

Negotiating the Challenges of Online Learning and Community-engaged Scholarship

There are many benefits to community-engaged scholarship. As academics, we have the opportunity to use higher education as a tool for democracy and a mechanism for enhancing social equity. As educators, community-engaged scholarship can give students “hands-on” experiences and practical skills development. As more programs move toward online curricula, community-engaged scholarship becomes more challenging. It is time consuming, and, if done poorly, might reinforce inequalities rather than promote social equity. Online students come from diverse locations, often work full-time jobs and have family responsibilities, and attend asynchronous classes, none of which lends itself to engaging in community projects.

Paving A Path Forward for Engaged Scholarship

Several recent Urban Affairs Review forum pieces have highlighted classroom practices that foster engaged learning by encouraging students, community organizations and policy makers to critically consider and potentially change some of the most complex issues our cities face. But engaged learning, particularly community-based service-learning, can cultivate more than positive communal outcomes. It can be a transformational experience for participants, especially students. In our forthcoming paper at the Journal of Nonprofit and Public Affairs, we lay out a roadmap for designing and executing democratic service-learning courses that generate critical citizenship and social justice advocacy behaviors in public affairs students. Here, we would like to share not only our findings but our process.

Changing Laws for Credit

“Your homework: Change public policy.” This was the daunting task I gave to the aspiring public and nonprofit leaders enrolled in my graduate policy course at Cleveland State University’s Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs. This wasn’t simply a pep talk; this task was their main assignment for the course. All semester long, the students were charged to work in groups to lobby for some state or local legislative or administrative change.

Making the Economic Development Process Accessible to Students

Economic development is a complex process by which local entities compete for development projects. Theory development in this area has ranged from descriptions of the economies of corporate clustering, transportation cost networks, central place theory, growth machine theory, and transaction cost theories to name a few. While these theoretical perspectives provide a basis for understanding “why” cities need economic development to survive in a highly competitive, fractured metropolitan space, these theories do little to show students the “how” of economic development decision-making.

An Applied Economic Development Project for Urban Politics Classes

I have the pleasure of teaching an upper-level political science course called “Urban Politics & Policy.” In order to help my students connect what they are learning to real-life situations, I have them (in small groups) create economic development plans for actual U.S. cities.